Welcome back

In the final entry of our StatFoundry series we’ll recap what we’ve learned and discuss how these learnings influenced the design behind the BIGRFS architecture, or Buildtime Ingestion and Generation for Runtime Filters and Suggestions, pronounced “Big Riffs”.

Believe it or not, the acronym came first.

The idea: By treating queries as composable LEGO blocks instead of sentences an LLM has to translate, StatFoundry introduces a chunk-based query system that lets users build complex graph database queries without knowing Cypher. It’s deterministic, testable, and enables real-time exploration of the dataset through smart suggestions.

Before we get into the nitty-gritty, let’s recap.

Wait, what are we doing again?

We’re building StatFoundry, which aims to be the easiest way to search for NFL stats on the internet.

At this point, we’ve tried enabling user-friendly graph database searches by translating a user’s question from natural language to something machine readable, like a Cypher query. This had mixed results.

Takeaways from Parts 1 and 2

1. Graph databases enable different kinds of queries

By replacing costly, multi-table JOINS in relational databases with cheap node-to-node relationships (or edges) in graph databases, we can enable deeper, more specific queries that would be otherwise cost prohibitive or cumbersome in SQL.

2. Google is the default for searching stats

The most commonly used method of searching for stats online that users (i.e., my friends) reported was simply Googling them.

The most common motive? Curiosity.

3. A user’s intent can (and will) get lost in translation

A user’s intent can be lost when ChatGPT translated an English question into a Cypher query, even though it was provided with the database schema and query examples as context.

Simple queries work great, but when translating the more complicated, multi-hop queries that make graph databases special—and by extension, our app, it’s not reliable enough.

As the complexity grows, so too do the opportunities for the LLM to hallucinate or misinterpret results.

Epiphany #1: LLMs are fuzzy, stats are not

I was eager to use AI to supercharge my as-of-yet unnamed Graph Based NFL Search App and make a trillion dollars in the white-hot sports technology market.

However, I quickly found that LLMs are much better at working with human language, where end-user expectations are more fluid, than with database query languages, where the machine’s expectations are rigid and deterministic.

Human language is fuzzy

By nature, human language is fuzzy, expressive and pliable.

Its non-deterministic nature enabled the evolution of language, which in turn enabled the evolution of thought, which got us all the way to this part of the blog where you’re thinking “WTF is Ben talking about?”

But human language is not deterministic. As LLMs are trained to imitate language, they inherit this fuzziness by design. This is why you might be seeing ontologies and knowledge graphs popping up more and more. They’re great tools for building determinism into the ambiguity of human language.

Statistics are not

Not only are statistics much less pliable than language, they are inherently deterministic.

A statistic is a recorded fact about something that happened. Once it’s recorded—Derrick Henry: 1,167 rushing yards in 2023—it’s fixed. There’s no room for interpretation. 1,167 ≠ 1,168.

For an application like ours, there is zero room for multiple interpretations of these statistical facts. Users have different, much narrower expectations when asking a machine for a table of numbers representing a fact versus asking for a summarization of a movie plot.

In “a game of inches”, everything is inherently precise.

Programming languages demand determinism too

Asking an LLM to translate English to Spanish is one thing. Asking it to translate English to Cypher or Java is another. Anyone who has vibe-coded for more than an hour can attest to this.

Yes, it compiles. It might even run!

But database query languages are deterministic by design. A database query either returns the correct results or it doesn’t. There’s no “pretty close” in SQL or Cypher.

LLMs, which are trained to be highly powered, language-predicting, educated-guess-machines, are not particularly well suited for this role. They’re built to be fuzzy and probabilistic but here we need them to be exact and deterministic.

Structured data vs unstructured queries

Here’s the fundamental mismatch: our data is highly structured (nodes, relationships, properties, all fitting within defined schemas), but natural language queries are unstructured and ambiguous.

When you say “Show me Patrick Mahomes’ best games,” what does “best” mean?

- Most passing yards?

- Highest passer rating?

- Most touchdowns?

- Most comebacks?

- All of the above?

An LLM has to guess. In fact, it’s incentivized to do so. And even if it guesses right 90% of the time, that 10% failure rate is unacceptable when users are trusting us to supply factual information.

The more I tried to wrangle an LLM into my stats search application, the more I felt I was slipping into the “solution in search of a problem” trap.

I decided to explore some “old-school”, LLM-free solutions…

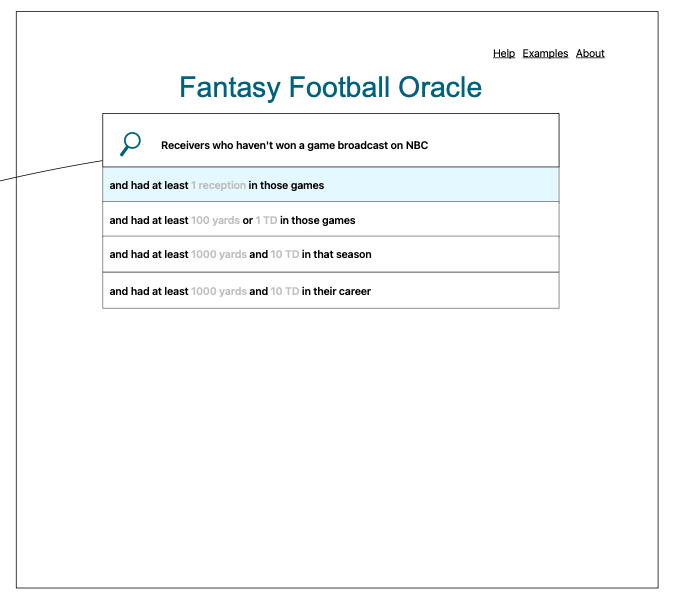

Epiphany #2: Agentic Users…

What if, instead of AI guessing the user’s intent, the users built the queries themselves, like some kind of autonomous being?

If we give users tools to write their own queries, we can “offload” the burden of intent deduction to the user. That’s a win for us. Less to worry about, less to test, and no hallucinations.

But more importantly, it’s a win for the user. Now that we’ve given them some of their agency back, we can utilize this agency to enable things like the dynamic suggestions originally sketched up before I got distracted by LLMs as the plug-and-play solution to “Google for NFL stats”.

These suggestions enable the user to explore the database while querying it. This is something we could never do if we just exposed an NLP pipeline for raw text.

But how do users “build” queries?

Obviously we’re not asking users to learn Cypher. But…what if they could write it without knowing they were writing it?

Instead, imagine this flow:

- User types: “Derrick Henry”

- System suggests: “rushing yards”, “touchdowns”, “games played”

- User selects: “rushing yards”

- System suggests: “in 2023 season”, “per game”, “top 10 games”, “against the Colts”

- User selects: “in 2023 season”

- Query complete: “Show me Derrick Henry’s rushing yards in 2023 season”

Behind the scenes, each selection is adding a chunk to a query chain. The user is composing a Cypher query without knowing it.

So where does this lead us? How do we enable suggestions? How do we ensure the suggestions are valid? How do these chunks ultimately compile into valid Cypher, without the aid of an LLM?

The Architecture: Query Chunks

I’ve buried the lede enough. This is where we solve the problem.

Much like the Graph Database said “Aha! What if I made the relationships first class citizens?”

We say “Aha! What if we made the query itself a first class citizen?”

What if we started treating the query like a composable input rather than a non-deterministic output?

What is a Query Chunk?

Chunks are the building blocks of our query building system. They are the LEGO blocks.

Each chunk is an object that represents a segment (or chunk) of a composable query.

A chunk contains:

- A templated human-readable representation of the segment

- A templated machine-readable representation of the segment (Cypher)

- Rules to determine which other segments can or can’t be linked to this segment

- A mechanism to fill in the English and Cypher string templates

- A mechanism to enable suggestions of chunks to link

export type Chunk = {

/**

* Templated human readable representation

* ex: Player's named {playerName}

*/

English: string;

/**

* Templated machine readable representation

* ex: MATCH (p:Player) where p.name = {playerName}

*/

Cypher: string;

/**

* Determines what can or cannot be linked

* ex: MATCH_START indicates the start of a MATCH clause

*/

QueryType: QueryType;

/**

* What data the chunk requires

* ex: `p`, a variable representing "player"

*/

Requires: Alias[];

/**

* What data the chunk provides

* ex: `p`, a variable representing "player"

*/

Provides: Alias[];

/**

* Slots are the mechanism to fill in templates.

* More on this later

*/

Slots: Slot[];

/**

* Simple Mechanism to enable suggestions

* Fuzzy match on strings

* ex: ["RB","running","running back","rush"...]

*/

SuggestionKeywords?: string[];

};The Type System

To make chunks composable, we need a type system. Here’s how it works:

Aliases

type Alias = {

Name: string;

AliasType: AliasType;

};

// In our system, these map to Node Labels in Neo4j

enum AliasType {

Player = "Player",

Team = "Team",

Game = "Game",

Season = "Season",

PlayerGame = "PlayerGame",

PlayerSeason = "PlayerSeason",

Play = "Play",

// ...

}The rule: Chunks can’t be added to the query unless the aliases in their Requires property exist in the ChunkChain’s Aliases property.

As the query is built, the List<Aliases> that a chunk exposes via the Provides property are aggregated and stored in the ChunkChain’s Aliases property so that they can be accessed by chunks that Require them later on.

Think of it like a dependency graph for your query.

QueryTypes

enum QueryType {

MATCH_START = "MATCH_START", // must be first

JUNCTION = "JUNCTION", // connects entities

FILTER = "FILTER", // narrows results

RETURN = "RETURN", // must be last

}This enforces query structure. You can’t return before you match. You can’t filter before you have something to filter.

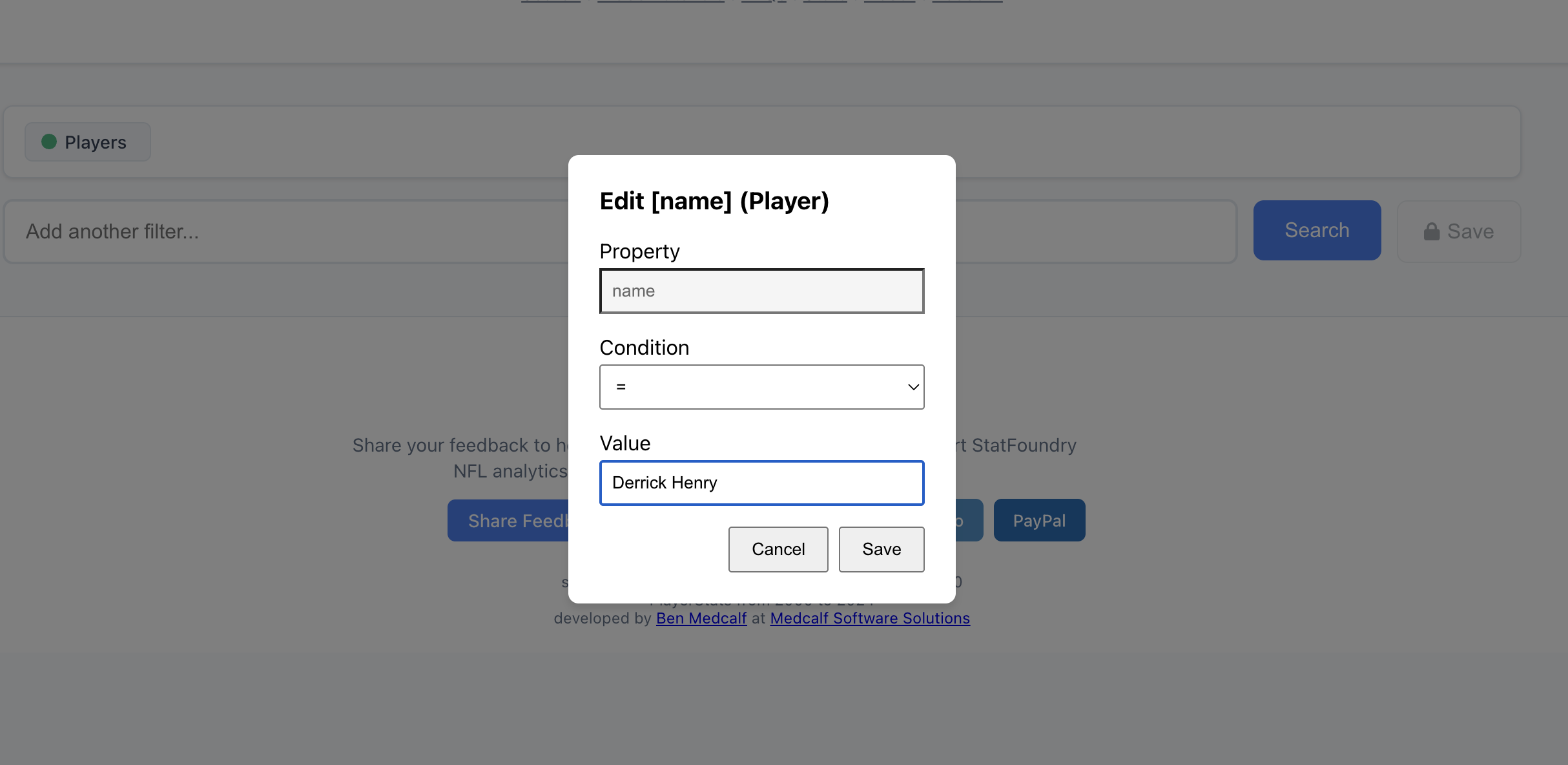

Slots

Slots are the variables in our query templates. They define what values are valid and where they can be used.

type Slot = {

Name: string;

Value: any;

SlotValueTypes: SlotType[];

};Slots In Action

// we use this enum to determine what we allow the user to fill slots with

export enum SlotType {

// entity properties

SelectPlayerProperty = "SelectPlayerProperty",

SelectPlayerPosition = "SelectPlayerPosition",

SelectTeamProperty = "SelectTeamProperty",

SelectGameProperty = "SelectGameProperty",

SelectSeasonProperty = "SelectSeasonProperty",

// compound properties

SelectPlayerGameProperty = "SelectPlayerGameProperty",

SelectTeamGameProperty = "SelectTeamGameProperty",

SelectPlayerSeasonProperty = "SelectPlayerSeasonProperty",

SelectTeamSeasonProperty = "SelectTeamSeasonProperty",

// filter properties

Filter = "Filter",

FilterCondition = "FilterCondition",

FilterValue = "FilterValue",

SelectPassingStats = "SelectPassingStats",

SelectPassingStatsGame = "SelectPassingStatsGame",

SelectPassingStatsSeason = "SelectPassingStatsSeason",

SelectFlexStats = "SelectFlexStats",

SelectFlexStatsGame = "SelectFlexStatsGame",

SelectFlexStatsSeason = "SelectFlexStatsSeason",

SelectPlayStats = "SelectPlayStats",

}The Chunk Chain

The ChunkChain is the data structure that manages the composition:

export class ChunkChain {

Head: ChunkNode | null;

Tail: ChunkNode | null;

Aliases: Alias[]; // the types (aliases) of entities we have available to use

English: string; // the merged segments of english

Cypher: string; // the merged segments of cypher

append(chunk: Chunk): ChunkNode;

pop(): ChunkNode | null;

toArray(): Chunk[];

insertAt(index: number, chunk: Chunk): ChunkNode; // for mid-chain updates

compile(): ChunkChain; // takes in segments and builds the final strings

updateChunkAtIndex(index: number, newChunk: Chunk): ChunkChain;

getNextValidChunksFromChunks(chunksToCheck: Chunk[]): Chunk[]; // the "Filter"

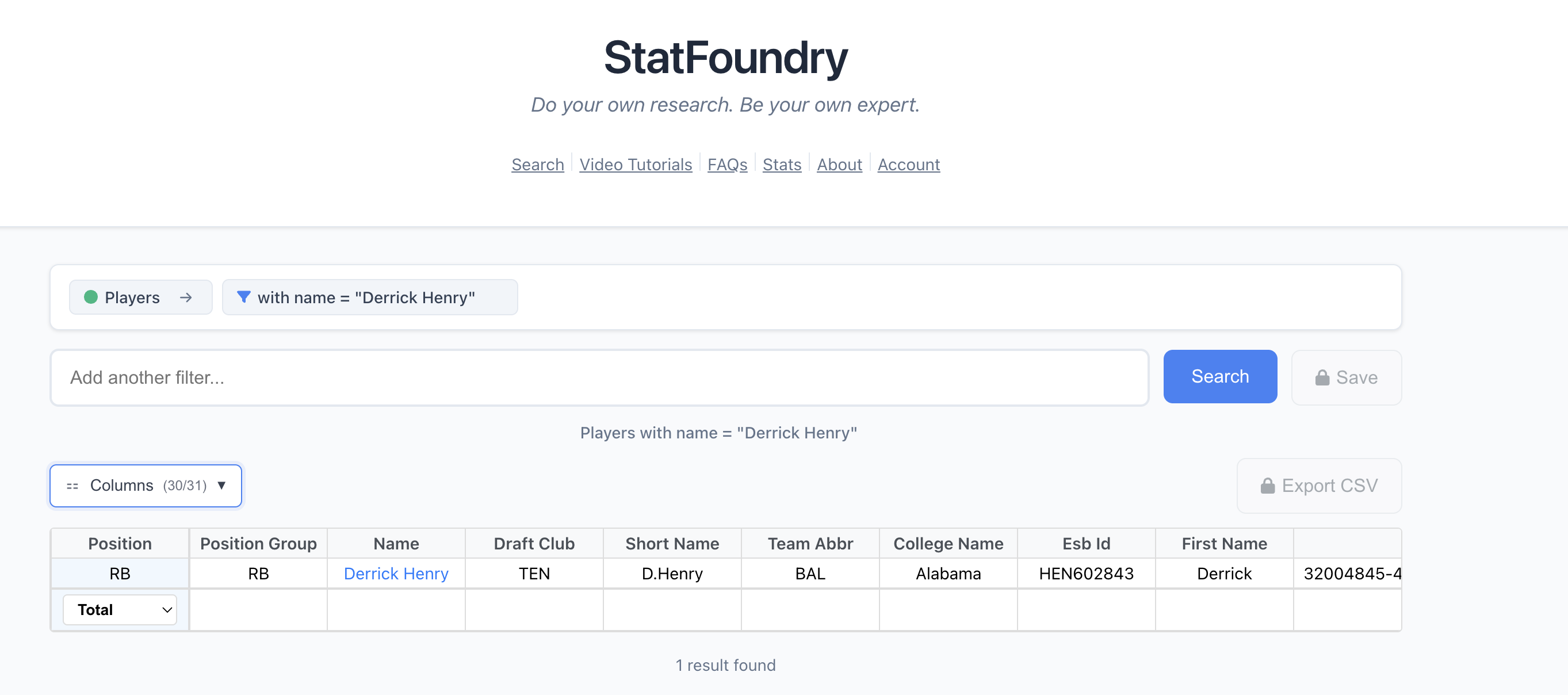

}Usage example

// "Show me rushing yards for Derrick Henry in 2023"

const chain = new ChunkChain();

// Step 1: User types "Derrick Henry"

chain.append(matchPlayerChunk);

// Provides: { Name: "player", AliasType: "Player" }

// Aliases now: [Player]

// Step 2: User selects "in 2023"

chain.append(filterBySeasonChunk);

// Requires: Player ✅ (we have it!)

// Provides: { Name: "season", AliasType: "Season" }

// Aliases now: [Player, Season]

// Step 3: User selects "rushing yards"

chain.append(returnRushingYardsChunk);

// Requires: Player ✅, Season ✅

// Provides: []

// Aliases now: [Player, Season]

// Compile and execute

const result = chain.compile();

console.log(result.English);

// "player Derrick Henry in 2023 rushing yards"

console.log(result.Cypher);

// "MATCH (player:Player {name: 'Derrick Henry'})

// MATCH (player)-[:PLAYED_IN_SEASON]->(season:Season {year: 2023})

// RETURN player.name, SUM(stats.rushingYards) as totalRushingYards"The validation function ensures type safety:

export function isValidNextChunk(

chunk: Chunk,

currentAliases: Alias[],

): boolean {

// Check if all required aliases are available

return chunk.Requires.every((required) =>

currentAliases.some(

(available) =>

available.Name === required.Name &&

available.AliasType === required.AliasType,

),

);

}

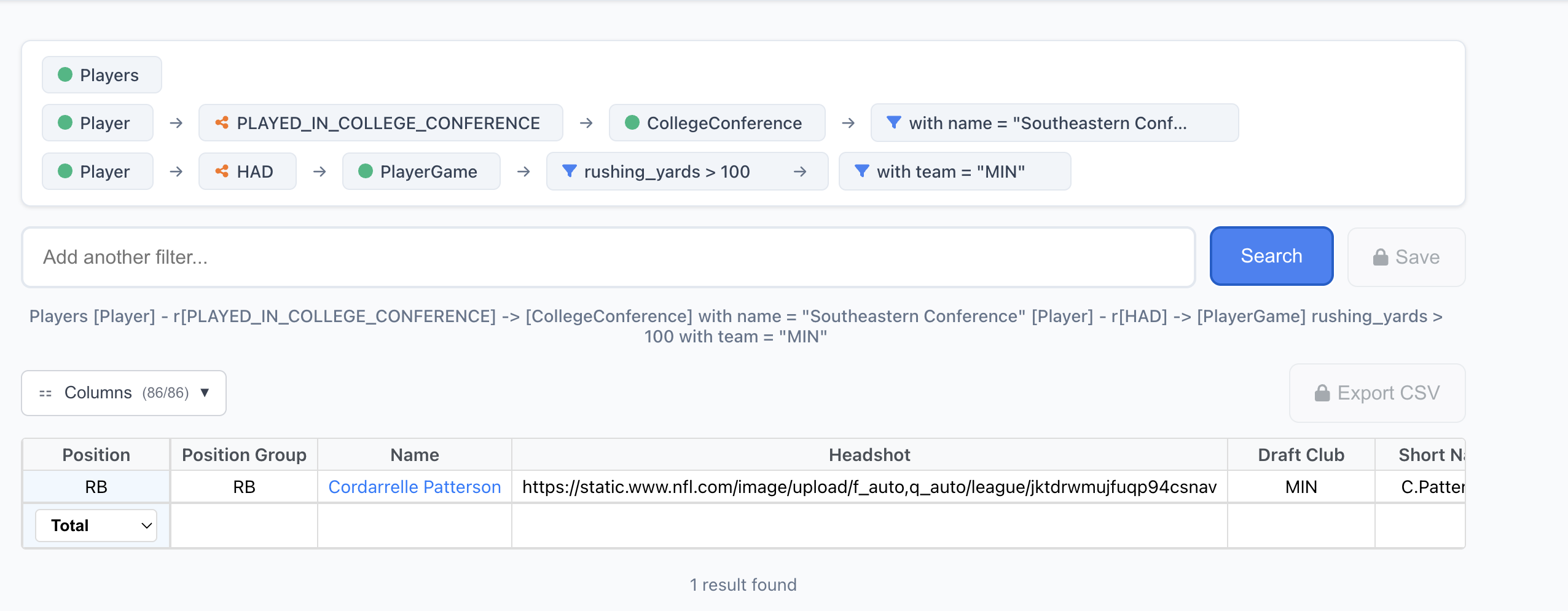

Match (green circle), Junction (orange graph) Filter (blue funnel).

BIG: Buildtime Ingestion and Generation

Now that we understand chunks, let’s talk about how they’re created. This is the “BIG” part of BIGRFS.

The problem with handwriting chunks

I could sit down and manually write every possible chunk for every possible query. But that would be:

- Tedious - hundreds or thousands of chunks

- Error-prone - easy to miss edge cases

- Hard to maintain - every schema change means rewriting chunks

- Impossible to scale - what about custom user queries?

The solution: Generate chunks from the schema

At build time, we:

- Ingest the Neo4j schema (node labels, relationship types, properties)

- Generate all possible chunks programmatically

- Validate chunk compatibility

- Index chunks for fast lookup

- Export to JSON for runtime use

Here’s the workflow:

// 1. Ingest schema from Neo4j

const schema = await ingestNeo4jSchema(neo4jConnection);

// 2. Generate chunks for ALL node types dynamically

const nodeChunks = schema.nodeTypes.flatMap((nodeType) =>

generateMatchChunksForNodeType(schema, nodeType),

);

// 3. Generate chunks for each relationship

const relationshipChunks = generateJunctionChunksForRelationships(

schema.relationships,

);

// 4. Generate filter chunks for each property

const filterChunks = generateFilterChunksForProperties(schema.properties);

// 5. Generate return chunks for each stat type

const returnChunks = generateReturnChunksForStats(schema.stats);

// 6. Combine and validate

const allChunks = [

...nodeChunks,

...relationshipChunks,

...filterChunks,

...returnChunks,

];

validateChunkCompatibility(allChunks);

// 7. Build suggestion index

const chunkIndex = buildSuggestionIndex(allChunks);

// 8. Export for runtime

exportChunksToJSON(allChunks, chunkIndex);Example: Auto-generating match chunks

function generateMatchChunksForNodeType(

schema: Schema,

nodeType: string,

): Chunk[] {

const chunks: Chunk[] = [];

const properties = schema.getPropertiesForNode(nodeType);

for (const prop of properties) {

chunks.push({

English: `${nodeType.toLowerCase()} with ${prop.name} \${${prop.name}}`,

Cypher: `MATCH (${nodeType.toLowerCase()}:${nodeType} {${prop.name}: '\${${prop.name}}'})`,

QueryType: QueryType.MATCH_START,

Requires: [],

Provides: [

{ Name: nodeType.toLowerCase(), AliasType: AliasType[nodeType] },

],

Slots: [

{

Name: prop.name,

Value: null,

SlotValueTypes: [SlotType[`Select${nodeType}Property`]],

},

],

SuggestionKeywords: [nodeType.toLowerCase(), prop.name],

});

}

return chunks;

}This generates chunks for every property of every node type automatically. Change the schema? Re-run the build. New chunks automatically generated.

Build-time benefits

- Single source of truth: Schema drives chunk generation

- No drift: Chunks always match database structure

- Fast iteration: Change schema, rebuild, done

- Type safety: Generated TypeScript types for all chunks

- Testing: Can validate all generated chunks before deployment

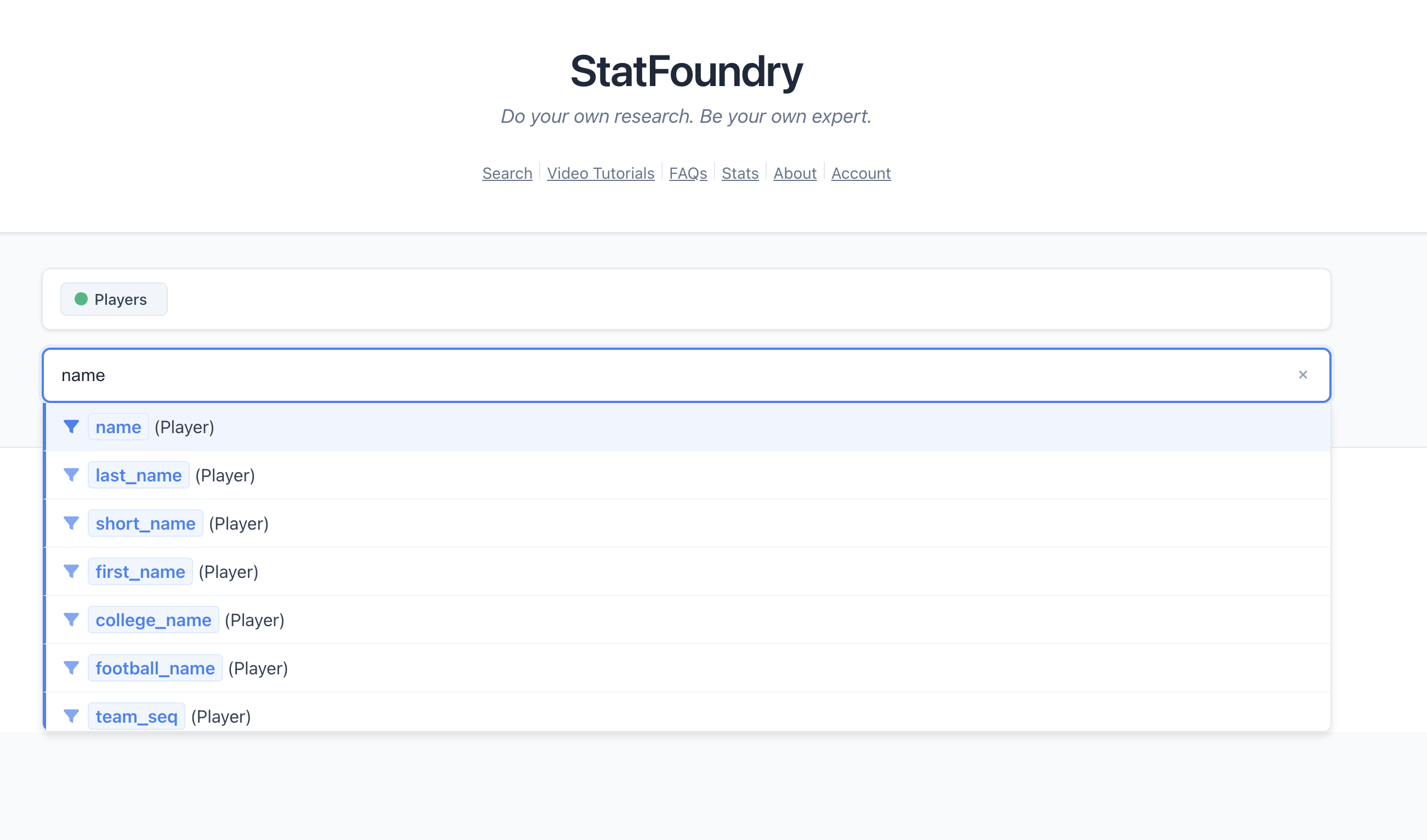

RFS: Runtime Filters and Suggestions

The “RFS” part handles the user experience—how chunks turn into suggestions that feel natural.

How suggestions work

- User types: “derrick”

- System filters chunk library by keywords using fuzzy search

- System validates which chunks are compatible with current query state

- System ranks suggestions by relevance

- User sees: “Derrick Henry (Player)”, “Derek Carr (Player)”, “Tennessee (Team)“

The suggestion pipeline

export function getSuggestions(

userInput: string,

currentChain: ChunkChain,

chunkLibrary: Chunk[],

): Suggestion[] {

// Step 1: Fuzzy search by keywords

const keywordMatches = fuzzySearchChunks(userInput, chunkLibrary);

// Step 2: Filter by compatibility

const validChunks = currentChain.getNextValidChunksFromChunks(keywordMatches);

// Step 3: Rank by relevance

const rankedSuggestions = rankSuggestions(validChunks, userInput);

// Step 4: Format for display

return rankedSuggestions.map((chunk) => ({

displayText: fillTemplate(chunk.English, chunk.Slots),

chunk: chunk,

confidence: chunk.relevanceScore,

}));

}Fuzzy search with Fuse.js

We use Fuse.js for fuzzy keyword matching:

import Fuse from "fuse.js";

function fuzzySearchChunks(userInput: string, chunks: Chunk[]): Chunk[] {

const fuse = new Fuse(chunks, {

keys: ["SuggestionKeywords"],

threshold: 0.3, // how fuzzy?

includeScore: true,

});

const results = fuse.search(userInput);

return results.map((r) => r.item);

}This handles typos and partial matches. “rshing” → “rushing”, “mahomes” → “Patrick Mahomes”

Beyond fuzzy keyword matching

Fuse.js is just the baseline implementation. The architecture supports much smarter suggestion mechanisms:

Semantic search: Instead of matching keywords, embed chunk descriptions and user input into vector space. Use cosine similarity to find semantically related chunks, even if the words don’t match.

Usage patterns: Track which chunks users select together. “Players who selected X also selected Y.” Amazon-style recommendations for queries.

Context-aware ranking: Weight suggestions based on:

- Current query context (what aliases are available?)

- User’s search history (what do they usually look for?)

- Popular queries (what do most users search?)

- Data availability (does this chunk have enough data to return meaningful results?)

LLM-assisted suggestion (optional): Use an LLM to suggest relevant chunks based on free-text input, but still require users to select from valid chunks. The LLM doesn’t write the query—it just helps you find the right LEGO blocks.

The key insight: fuzzy keyword search is just the dumbest possible implementation. The chunk architecture doesn’t care HOW you suggest chunks, just that you filter them by compatibility before showing them to users.

The validation filter

ChunkChain.prototype.getNextValidChunksFromChunks = function (

chunksToCheck: Chunk[],

): Chunk[] {

return chunksToCheck.filter((chunk) => isValidNextChunk(chunk, this.Aliases));

};This is where the magic happens. Only chunks whose requirements are satisfied by the current query state make it through.

Example:

-

Current state:

[Player] -

Candidate chunk requires:

[Player, Season] -

Result: ❌ Filtered out

-

Current state:

[Player, Season] -

Candidate chunk requires:

[Player] -

Result: ✅ Valid suggestion

Making it feel natural

The suggestions need to feel conversational, not like you’re programming. We achieve this through:

- Natural language templates: “in 2023” not “WHERE season.year = 2023”

- Smart defaults: Common queries suggested first

- Context awareness: Suggestions change based on what you’ve already selected

- Progressive disclosure: Don’t show 100 options, show the 5 most likely

What this really is: User fiendly path traversal

When you use Neo4j (or any graph database), you’re essentially walking paths through nodes and relationships. That’s what Cypher does, it describes paths to traverse.

But people don’t think in graphs. They think in questions:

- “Who were the top rushers last year?”

- “Which teams has Patrick Mahomes beaten most often?”

- “Show me tight ends with over 1000 yards in a season”

BIGRFS gives people the ability to traverse graphs without knowing anything about graphs. Each chunk represents a valid “step” in a graph traversal. When you chain chunks together, you’re building a path through the data—you just don’t realize it.

This shifts the emphasis to data modeling

This is why BIGRFS only works if your data model is good.

The chunks can only suggest valid traversals if:

- The relationships actually exist in your graph

- The relationships are semantically meaningful

- The node labels and properties are intuitive

You can’t hide bad data modeling behind clever UI. If your graph has a Player -[:WEIRD_LINK]-> Game relationship that doesn’t make semantic sense, chunks will suggest traversing it, and users will get confused.

The architecture forces you to care about data modeling, which is exactly where the effort should go. Graph databases are only as good as the graphs you model.

This is a feature, not a bug. If your schema is clean and intuitive, BIGRFS makes it explorable. If your schema is a mess, BIGRFS will expose that mess to users through nonsensical suggestions.

Why BIGRFS works

Let’s recap the benefits:

Deterministic ✅

- No LLM guessing

- Same input → same output

- Fully testable

Fast ✅

- Chunks pre-generated at build time

- No API calls

- Instant suggestions

Explorable ✅

- Users discover queries through suggestions

- Learn the schema without documentation

- Guided journey through the data

Maintainable ✅

- Schema-driven generation

- Chunks auto-update with schema

- Type-safe end to end

Scalable ✅

- Handles complex multi-hop queries

- Modular chunk library

- Easy to add new query patterns

Problems and limitations

Let’s be honest about what doesn’t work perfectly yet:

1. You still gotta know the schema (kinda)

While suggestions help, users still need some mental model of what data exists. If you don’t know that “rushing yards per game” is a thing we track, you won’t know to look for it.

Potential solution: Add a “popular queries” section or guided templates for common questions.

2. Edge cases are tedious

While the common path (match player → filter season → return stats) is covered beautifully, weird edge cases still require custom chunks. Things like:

- “Players whose team changed mid-season”

- “Games played in overtime”

- “Comparing stats across different eras”

Each of these requires special handling.

Solution: User-generated query library

Let users save and share complex searches publicly. Edge cases get solved once, used by many. Popular saved queries also reveal what chunks are missing from the core library—creating a feedback loop between community usage and system development.

3. The suggestion UX is critical

If the suggestions don’t feel natural, the whole system falls apart. Getting the ranking, timing, and display of suggestions right is UX design work, not just engineering.

We’re still iterating on this.

Future enhancements

Some things I want to add:

1. Chunk composition editor Let advanced users see and edit the chunk chain visually, like a node graph.

2. Saved queries as chunks Turn frequent user queries into reusable chunks that others can discover.

3. Natural language input alongside chunks Use an LLM to suggest chunks based on free-text input, but still let users compose deterministically.

4. Query templates Pre-built chunk chains for common questions (“Who led the league in rushing?”)

5. Collaborative chunks Let users share and remix chunk patterns.

Conclusion

BIGRFS—Buildtime Ingestion and Generation for Runtime Filters and Suggestions—is an architecture for building deterministic, explorable query systems on top of graph databases.

By treating queries as composable chunks instead of sentences to translate, we get:

- Reliability: No LLM hallucinations

- Speed: Instant suggestions, no API latency

- Discoverability: Users explore data through suggestions

- Maintainability: Schema-driven generation

It’s not perfect, but it solves the core problem: letting users ask complex questions without learning Cypher or hoping an LLM guesses correctly.

And yes, the acronym really did come first.

Next up: Part 4, where we talk about the actual UI and what it’s like to use this thing in practice. Stay tuned.